(December 9) We stop to take pictures at a spot overlooking the Sacred Valley of the Incas, located roughly between the old Inca capital of Cusco and Machu Picchu. It is named for the Urubamba River which was called Willkamayu (“sacred river”) in Quechua.

It is a fertile valley, famous for a breed of corn with extra-large kernels that grows nowhere else.

The Posada del Inca in Yucay in the Sacred Valley is one of the most picturesque hotels that I have ever stayed at, located in what was originally a 17th century monastery.

(December 10) The town of Ollantaytambo was once a large Inca settlement. Today in its narrow streets we can see how the Spanish settlers built their houses on top of the ruins of the buildings they had seized from the Incas.

Much of the Inca’s original drainage system is still intact. Without it erosion during the rainy season would have destroyed the buildings long ago.

Here we can see two types of Inca stonework. The upper part is in a “rural” style with loose-fitting stones held together with clay mortar. The lower part shows a more sophisticated technique with stones carved to fit together precisely with no need for mortar.

In the 1950s when my parents lived briefly in Peru the people of the mountains wore traditional native clothing as a matter of course. These days it is commonly worn by women who pose for tourists in exchange for tips.

The interior of a traditional Inca home.

No Inca home would be complete without a collection of guinea pigs.

The Incas used niches in the wall to display sacred items and relics of honored ancestors.

Dried meat. The English word “jerky” comes from the Quechua language. So do the words “coca”, “condor”, “guano”, “llama”, “puma”, “quinine” and “quinoa.”

It’s common to speak of the “Inca people” and the “Inca Empire” but it would probably be more accurate to speak of the “Quechua people.” The “Inca” was the title of their semi-divine ruler. I’m going to stick with the common usage though.

On the slopes of the mountains that rise above Ollantaytambo we can see some of the agricultural terraces that cover much of the Andes.

The steep Andes mountains bisect Peru and occupy much of its territory. To the west are the flat coast-lands which include some of the world’s harshest deserts, though parts watered by rivers are fertile. To the east is the impenetrable Amazon jungle. Altogether only about 3% of Peru is naturally suited for agriculture.

To solve this problem the pre-Columbian natives built vast numbers of terraces. Without this huge increase in the amount of farmland it is unlikely that Peru could have become the center of a great empire encompassing most of the west coast of South America.

The terraces are not cut into the mountain–the topsoil would have been washed away during the first rainy season. Instead the natives built a retaining wall along the slope of the mountain, then filled the interior with layers of stone and gravel, with topsoil on the top. The resulting structure could last for centuries with little maintenance.

The Spanish conquerors settled mostly in the lowlands where they rounded up the natives and put them to work. Up in the mountains the natives continued to live relatively unmolested, farming the terraces and minding their own business. The Spaniards had no idea how many were up there.

However they didn’t build new terraces. Building a terrace required a large number of workers. If the Spaniards had looked up and seen a large Indian work party building a terrace they would have sent soldiers to round them up. So even though many terraces are still farmed today the people have forgotten how to build them.

On the side of the mountain we can see the remains of a storehouse where the Inca rulers used to keep supplies of food and weapons for emergencies.

The Incas were a bit like the ancient Romans: great engineers and organizers. As with the Romans their rule depended largely on their ability to move large numbers of lightly equipped troops rapidly around their empire on a network of “trails” which in some places were actually narrow roads. For this to work they had to keep supplies at strategic points.

Ollantaytambo was built around a large temple complex which the Spaniards called a “fortress” because it was the site of one of the last battles between an Inca army and the Spanish. Unlike most such battles the Incas won this one.

Before the battle they had dammed the small river that separated the temple complex from the rest of the town. In the middle of the battle they flooded the battlefield, negating the advantage of the Spanish horses and muskets. The Spaniards decided to make a tactical retreat back to Cusco.

While the Spaniards waited for reinforcements the Inca warriors destroyed the Inca trails that ran near the town, gathered up all the portable gold and silver items, and escaped over a mountain pass into the jungle.

There was one important long-term effect: because they cut the trail from Cusco to Machu Picchu the Spaniards never found Machu Picchu. Its location remained unknown until the 20th century.

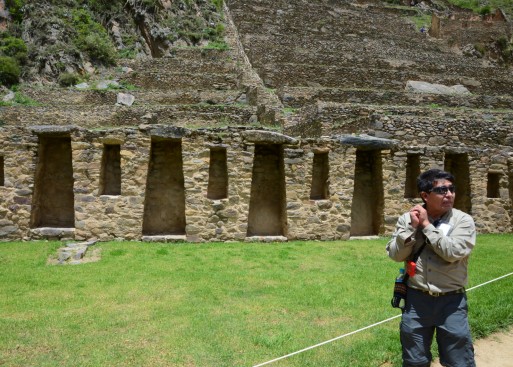

Though the Spaniards attempted to destroy the temples significant parts remain. The small niches in this wall probably held sacred gold and silver icons. The large niches may have been used to display the mummies of prominent people on special occasions.

An ancient fountain fed by underground pipes that run far up the mountain. The actual source of the water is unknown. The Incas considered the location of their water supplies to be a deep military secret. They themselves, when besieging a town, would routinely try to poison the water.

A trench dug by archeologists reveals a water conduit that predates the Incas.

The town of Chincheros is famous for its traditional weavers.

Local women demonstrate traditional weaving techniques.