October 24, 2011

Yoshinogari is located in an isolated farming area in northwestern Kyushu, but it was once an important center of early Japanese culture. This was the site of a major settlement during the Yayoi Period (approximately 300 BCE – 300 CE) during which rice farming and metalworking were introduced into Japan.

Archeological excavations beginning in the 1980s have shed a great deal of light on this early stage in Japan’s history.

Due to the great public interest in the site a park has been constructed reproducing how the site probably looked in the late Yayoi Period.

The reconstruction is based on the archeological evidence as well as contemporary Chinese descriptions of what they called the “Land of Wa.”

The most important part of the settlement, an area of almost 100 acres, was surrounded by a long wooden fence. The main entrance resembles a simplified torii, a resemblance emphasized by the fake birds (tori) placed above it.

(A popular bit of Japanese folk etymology holds that the word “torii” originally meant “bird perch.”)

Inside the fence there was a moat. Rows of sharpened stakes were placed behind the moat.

Not far from the main entrance was the “Southern Inner Palace” which served as the settlement’s central administrative complex. Not satisfied with the outer defenses that we have already seen, this complex had its own higher fence with an inner moat and watchtowers.

The main gate also included a platform where guards armed with bows could challenge vistors.

The Southern Inner Palace included the residences of the Ou (king), the Taijin (chief officials) and their wives. (These are Chinese terms. There is no way to be sure what the Yayoi people called them since they had no written language.)

The fanciest house belonged to the Ou or king. (“Fancy” is a relative term. This was basically a one-room pit house.)

Next to it is the house of the King’s wife. Among the aristocrats it was customary for husbands and wives to have separate houses.

Servants would prepare meals in this cookhouse for the Ou and Taijin.

This covered area in the center of the complex was used for meetings and assemblies.

Not far away is the “Northern Inner Palace” which was used for religious ceremonies. Like the Southern Palace this had its own fence, inner moat and watchtowers, as well as an additional inner fence.

This building was aligned with the sunrise on the summer solstice and the sunset on the winter solstice. Presumably it was used for some sort of solar rituals.

It seems to have been torn down and rebuilt many times. This is suggestive of the old Shinto practice of tearing down and rebuilding shrines on a regular basis to get rid of accumulated impurities.

This was the residence of the High Priestess, who probably never left the complex.

The building in front of it housed the High Priestess’s most senior servants.

At the center of the complex was the settlement’s largest building, an elevated structure used for important ceremonies.

In the building’s main hall the High Priestess presides over some sort of ceremonial meal with her acolytes.

In a smaller room at the top of the structure a more esoteric ceremony takes place. The High Priestess will enter a trance and bring back messages from the ancestral spirits.

A group of elevated storehouses just outside of the Northern Palace stored rice and supplies for large ceremonies.

In houses just outside of the Northern Palace servants of the High Priestess raised silkworms and brewed sake for ceremonies.

A bit farther north is the Northern Burial Mound which was used during the Middle Yayoi Period for the burials of high-ranking persons. Later it became a site for ancestor worship.

Some of the dead were buried in wooden coffins, but often the bodies were sealed in large earthenware jars. These jars tended to do a good job of preserving the artifacts buried with the bodies, making this a treasure-trove for archeologists.

A ring of storehouses surrounded the central marketplace.

Armed guards watched over the marketplace from a raised platform in the center.

Probably the market tended to attract suspicious characters from outside of the Ou’s domain.

Next to the guard platform was the administration building. From the platform on top flags and drums would announce the opening of the market. Vendors had to apply to the officials inside for permission to sell their goods. Presumably they paid a fee for the privilege.

Here is a village inhabited by the common people: simple farmers and craftsmen.

The houses may seem larger than those in the Southern Palace, but of course they had to be shared by an extended family.

Many of the items discovered by archeologists can be viewed in the on-site museum. The pictures below are taken from the excellent English-language brochure.

Pottery in the Early Yayoi Period resembled that of the earlier stone-age Joumon period.

However it was accompanied by polished stone tools similar to those used at the time in Korea for rice farming.

The items found in the Northern Burial Mound reflect the more advanced culture of the Middle Yayoi Period. Grave goods included numerous cylindrical glass beads and short bronze swords.

Bronze weapons were probably used for ceremonial purposes and as symbols of authority.

Other treasures include bronze coins from China.

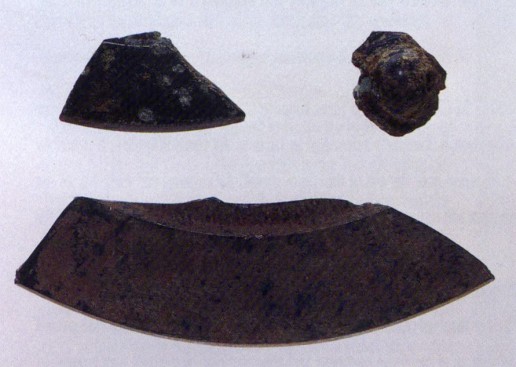

Pieces of bronze Chinese mirrors. The mirrors may have been deliberately broken as part of a funeral ceremony.

Smaller, cruder bronze mirrors were made in Japan in imitation of the ones from China.

Surviving iron artifacts seem cruder and more utilitarian, including simple axe heads, spades and scythes.

Many bodies show signs of warfare. This skeleton is missing its head and has deep cuts in the wrist and shoulder bones. Other bodies had stone arrowheads embedded in them.

For more about the Yayoi period see my essay on the Shinto religion.