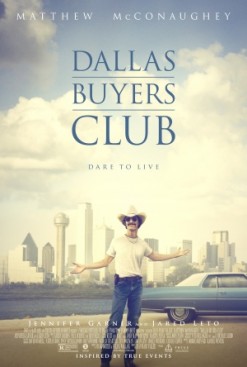

Dallas Buyers Club (IMDB) is a powerful but somewhat tendentious movie based loosely on a true story. It features notably strong performances by Matthew McConaughey and Jared Leto.

Dallas Buyers Club (IMDB) is a powerful but somewhat tendentious movie based loosely on a true story. It features notably strong performances by Matthew McConaughey and Jared Leto.

In 1985 Ron Woodroof (McConaughey) is a hard-living electrician and occasional rodeo cowboy, addicted to cocaine and casual sex. When he is diagnosed with AIDS he faces the prospect of certain death. No treatment has been approved in the United States. There are some drugs that are available in other countries which have shown some promise in preliminary studies, but Americans cannot legally obtain them.

So Ron partners with a flamboyant transvestite named “Rayon” (Leto) to form a “buyers club” of AIDS patients who pool their money to legally buy drugs in other countries and illegally smuggle them into the United States.

Jennifer Garner plays a sympathetic doctor who initially opposes the club but becomes convinced of its value and has a sort of quasi-romance with Woodroof. This part feels totally fictitious–a character inserted by a script doctor to make the movie more audience-friendly. (The main characters, were they not suffering from a fatal illness, would be fairly unlikeable.)

The movie’s main point is hard to argue with. Only the most heartless bureaucrat would say that people with a fatal disease with no approved treatment should be forbidden to experiment with drugs that might help them. Since such heartless bureaucrats do exist I can’t complain when the movie portrays them as villains.

But the movie does take some cheap shots. It rails against double-blind trials which deny the experimental drug to half the subjects. But these trials are the only reliable way to determine whether a treatment really does work. Without them doctors would still be prescribing snake oil.

Having it both ways, the movie also claims that the FDA was too quick to approve AZT, the first drug approved to treat AIDS. It had very dangerous side effects in the high doses originally prescribed. (Today it is commonly given in smaller doses in combination with other drugs.) It is suggested that the FDA approved such a dangerous drug only because it was in cahoots with the drug company.

We get the standard Hollywood indictment of drug companies. They are evil because they want to profit from the drugs that they have shepherded though the long and expensive approval process. They are careless of patient safety. But they are also evil because they don’t provide more drugs faster.

There is obviously a policy tradeoff here. Defenders of the American system which makes it difficult and expensive to get new drugs approved always point to the case of Thalidomide, which was approved in Europe for use as a tranquilizer but then turned out to cause severe birth defects. This argument sounds less convincing when applied to drugs to treat fatal diseases.

America’s draconian restrictions on prescription drugs are closely tied to the country’s century-old war on recreational drugs. Too be sure, few people would want to go back to the old days when anyone could walk into a drugstore and buy a bottle of heroin pills for a few pennies, but we have gone so far in the other direction that a lot of sick people suffer unnecessarily. In countries whose traditions are less puritanical new treatments tend to be available faster and cheaper, though perhaps with a bit more risk.