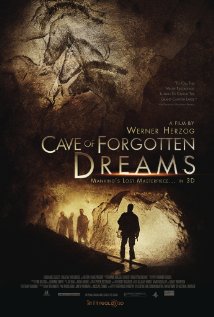

Cave of Forgotten Dreams is a documentary by Werner Herzog that gives a fascinating glimpse of a culture that existed so long ago that it is hard for the mind to grasp it.

Cave of Forgotten Dreams is a documentary by Werner Herzog that gives a fascinating glimpse of a culture that existed so long ago that it is hard for the mind to grasp it.

The Chauvet Cave in southern France, discovered in 1994, contains the worlds oldest and best-preserved cave paintings. The site is so fragile that it was immediately declared off-limits by the French government. Only a handful of scientists are allowed to work there for a few weeks each Spring. Because of dangerous levels of carbon dioxide and radon no one is allowed to spend more than 4 hours per day in the cave.

Herzog received special permission to film a documentary in the cave, but he was restricted to a crew of 4 people including himself. They were required to wear special contamination-free clothing and use custom-made handheld cameras and low-temperature lights. They were forbidden to touch anything and had to remain on a narrow walkway–the soft clay floor is still littered with the bones of cave bears, fragments of charcoal from ancient torches and human and animal footprints.

The oldest of the paintings was made almost 33,000 years ago and Ice Age humans continued to visit the cave and leave drawings for about 5,000 years, until the entrance was sealed by a rock slide, preserving the contents in pristine condition.

(Contrary to popular myth these people were not “cave men” and did not live in caves. Their lifestyle was probably similar to modern hunter-gatherers in northern climates and they probably used the cave for religious ceremonies.)

It is hard to grasp how old these paintings are. If we pretend that the oldest painting was made one hour ago, then the Great Pyramid of Giza was built about 8 minutes ago. Otzi the Iceman, the Stone Age hunter whose body was found frozen in a glacier in the Alps, died 10 minutes ago. Even the ancestors of the Native Americans probably crossed the Bering Straight 30-40 minutes ago.

In spite of their immense age the paintings are in amazing condition with fine details easily visible. They mostly depict the large animals that filled southern Europe at the time: bison, reindeer, wild horses, aurochs, mammoths, wooly rhinos with long double horns, giant cave bears and majestic cave lions. The animals are shown in great detail with vivid depictions of movement. The bright eyes of the horses and lions make them look almost alive.

A massive skull of a cave bear sits on a large semi-rectangular rock that resembles an altar, further suggesting that the cave was used for religious ceremonies.

The artists left numerous hand prints in red paint on the walls, especially by the mouth of the cave. Aside from these there is only one depiction of a human figure and it is rather disturbing: the torso and legs of a woman apparently being embraced by a bison. (This calls to mind the much later Greek myth of the Minotaur, a half-human monster produced by the mating of a woman and a bull.)

Hoping to learn more about these people, Herzog travels to the Schwäbische Alps in southwestern Germany, which does not have cave paintings but does have numerous artifacts from the same time period. A glacier-free corridor connected southern Germany with southern France, and hunter-gatherers probably traveled between the regions regularly.

The artifacts include carvings of animals in ivory and bone, done in a style rather reminiscent of the cave paintings. There are numerous “Venus” figures of women with gigantic breasts, bellies and hips. Particularly interesting are the little bone flutes which use a pentatonic scale, which Herzog claims is the basis of Western music. An archeologist manages to use one to play the first few bars of The Star-Spangled Banner. (Actually this is the simplest possible musical scale and is probably ancestral to all music in every culture.)

Here as in other places Herzog manages to suggest that the cave painters were ancestral to modern Europeans and their art was the beginning of European culture. This initially struck me as a bit unlikely. Indo-European languages probably entered Europe about 5000 years ago, so if the cave painters were ancestral to any modern Europeans it would have to be the Basques.

However even this fails to appreciate the length of time involved. In the space of 30,000 years the descendents of the cave painters could easily have died out. Alternatively they could have migrated back and forth across the continent several times, possibly interbreeding with all the major ethnic groups of Eurasia. Unless we discover some frozen genetic samples from the cave painters, we will probably never know.